Understanding beer conditioning is vital for your cellar manager and it makes sense for your bar team to be aware of this important process too.

Setting up cask beer on a stillage is ideally done as soon as it arrives in your cellar. Ideally you will place your cask on a sprung loaded auto-tilting stillage. As the cask empties it will automatically tilt to ensure that you get a free flow of beer to the beer engine on the bar. Alternatively, you may be using triangular wooden chocks on which the cask rests. The most common arrangement is two chocks at the front and one at the rear. As the cask empties, you will need to push the rear chock forward in order to tilt the cask. Check that the cask is horizontal with the keystone at its lowest point and don’t be tempted to tilt the cask at the start as this can result in a loss of beer. As the cask may have rolled on dirty floors you will need to clean both the shive and keystone with sanitizer or diluted line cleaner. A stock rotation system to ensure that older beer is used first can be as simple as a chalk number on the front of the cask.

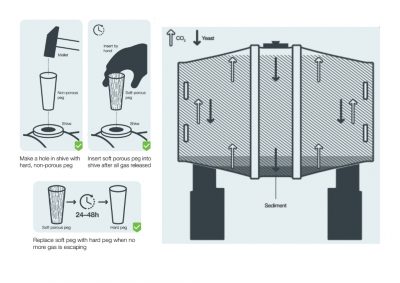

Allow time one or two days for the beer to drop bright. 48 hours before you want to serve the beer, use a mallet to drive a hole through the shive. You can use a punch, car valve or a clean hard spile (peg) to do this. Certain ‘lively’ beers or warm conditions may result in beer escaping from the shive so be ready for this. A venting tool which captures escaping beer can be used in extreme cases. Hand push a soft, porous spile into the shive and let the beer condition according to the brewery’s recommendation – normally 24 to 48 hours. Check the soft spile and replace it if it becomes blocked. When no more gas escapes from the soft spile, replace it with a hard spile. Next, use a mallet to insert a clean tap into the clean keystone. Check that the valve is at the top and use two firm blows of the mallet to ensure the tap is fully home. A gentle tap with the mallet can be used if there are any leaks around the keystone.

Conditioning

- Cask ale must be vented in order that it can be ‘conditioned’

- When the cask leaves the brewery, it contains sugar and yeast

- The yeast ferments the sugar into alcohol, with carbon dioxide as a by-product

- Some carbon dioxide that remains in the solution gives the beer its bubbles and frothy head, also known as ‘condition’

- During the conditioning process, the hops, malt and yeast in the beer mature and develop into subtle flavours that characterise a perfect cask beer

- The sediment must not be disturbed once it has settled

- The process of conditioning (also known as ‘secondary fermentation’) lasts between three and seven days

In future blogs I will explain about vertical stillage methods such as spears and cask widges as well as the process for testing the beer before it is put on sale.

| Brett says: “The secondary fermentation is an important part in the beer conditioning process. It allows additional flavours to develop within the beer. Do not be tempted to make any short cuts in terms of timing or hygiene. Well kept beer will keep your customers coming back for more and telling their friends about the great beer on sale in your pub.” |